Four Ways To Reframe Democracy in America

In today’s post, I endeavor to connect the dots between two troubling patterns. The first involves our reactions to the relentless storms of our national politics. We are already consternated by the thunderclouds forming around the 2024 presidential election, which is shaping up to be a rematch of the wrenching 2020 contest. The second development is the epidemic of loneliness and isolation, which has made our society more vulnerable to co-morbidities like corroding trust, senseless violence, and deaths of despair. How might these patterns relate to and reinforce each other?

I was recently prompted to grapple with this question by my friend Eric Liu. In June, at a Civic Collaboratory Eric hosted with the stellar team at Citizen University, he kicked things off by reminding us of one of Alexis de Tocqueville’s central insights. Given the broad equality of conditions and individualistic ethos of democracy in America, it can give rise to a sense of loneliness. Citizens living in such a democracy, Tocqueville observed,

“Become accustomed to thinking of themselves always in isolation and are pleased to think that their fate lies entirely in their own hands. Thus not only does democracy cause each man to forget his forebears, but it makes it difficult for him to see his offspring and cuts him off from his contemporaries. Again and again it leads him back to himself and threatens ultimately to imprison him altogether in the loneliness of his own heart.”

Eric had me at Tocqueville, our inspiration here at The Art of Association. But he went on to pose two provocative questions that I have been mulling over ever since:

Is the way we are practicing democracy contributing to the epidemic of loneliness?

What should we do differently to foster social connection and cohesion?

I jotted down some preliminary answers to these questions in my notebook when Eric first posed them. Then, a few weeks ago, I had an opportunity to workshop my ideas in a discussion organized by A More Perfect Union: The Jewish Partnership for Democracy.

A More Perfect Union is a promising startup that seeks to rally civic leaders and institutions in the Jewish community to strengthen U.S. democracy. It has articulated two compelling priorities–“in the short term: protect electoral democracy,” and “in the long term: rebuild a strong, resilient democratic culture.” I focused my remarks on the latter. But I also proposed to the group that, paradoxically, realizing their short-term priority for protecting elections might ultimately depend on securing their long-term goal at the cultural level.

Our narrow understanding of democracy in America

I’m increasingly convinced that many of us working to shore up democracy are hampered by a cramped conception of it. In our tunnel vision, the next presidential election, and the control of government ostensibly determined by it, are paramount. That we are so deeply polarized–another of our core assumptions–makes each national election “the most important of our lifetimes.” The fate of the republic thus continually hangs in the balance in what has become a running series of apocalyptic showdowns.

This pervasive understanding is not wrong so much as it is incomplete. It emphasizes aspects of democracy that reinforce our feelings of fear, contempt, resignation, and atomization. It de-emphasizes aspects that could give us a sense of hope, dignity, agency, and solidarity.

I understand–though I lament–why partisans, activists, and media commentators who benefit from the cramped conception of democracy seek to keep us transfixed by the reality show of our national politics. But we don’t have to adopt their overly narrow vantage point. We certainly don’t have to espouse it with an urgency that inadvertently worsens rather than resolves the dangers we worry about, not to mention our growing sense of isolation.

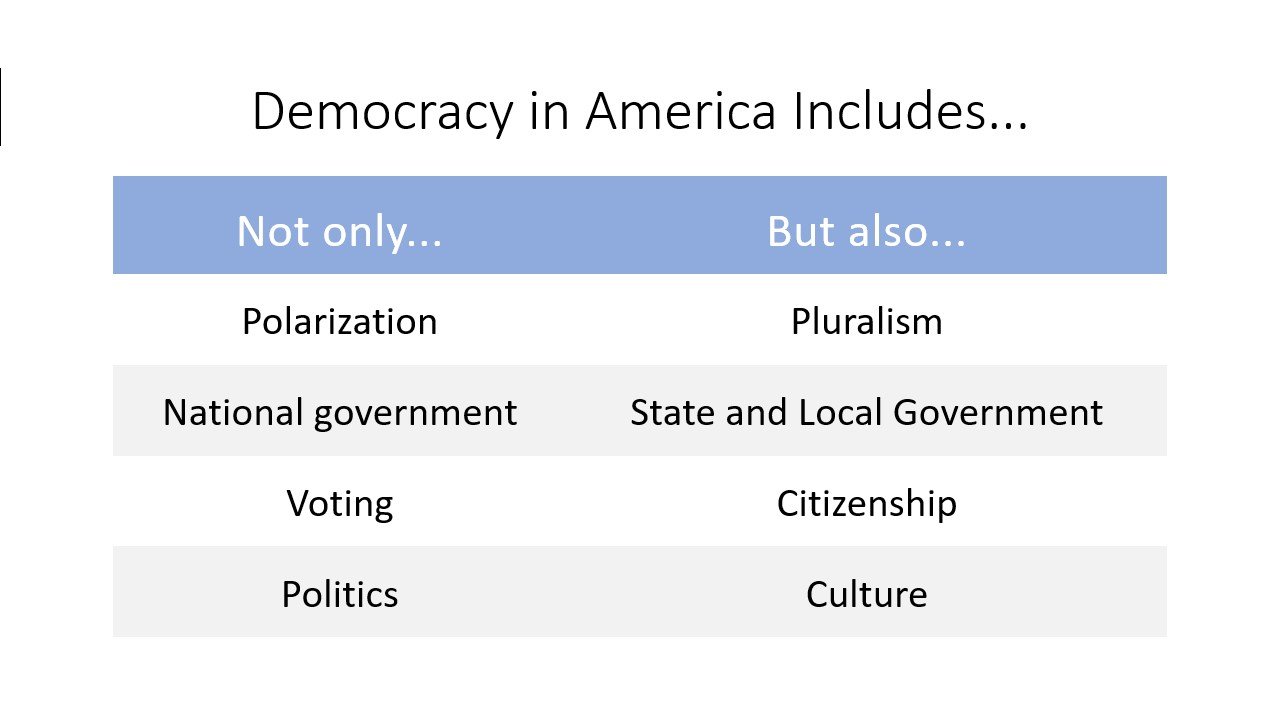

We need to pull the camera back and reframe democracy in America. We should do this not by glossing over sobering realities or including untested ideas, but rather by seeing age-old features of our democracy in a new light. This more holistic way of seeing democracy, in turn, illuminates ways to bring out its best features and counter the loneliness that is apt to accompany it. The table below summarizes four of the most important reframings, which the rest of the post then fleshes out.

Pluralizing our polarization

Polarization is a familiar story but only a partial one. It keeps us from seeing the substantive differences and competing factions that exist within the two major parties, as well as the still considerable common ground between them. We come to regard the opposing political sides as monoliths defined by their most extreme and outspoken outliers. And no wonder: A recent study found that conflict entrepreneurs in Congress get 4x more media coverage than bipartisan problem solvers. Even so, as James Curry and Frances Lee have documented, the vast majority of laws that Congress enacts continue to be supported by large bipartisan majorities in both chambers.

The polarized framing of politics in our media and society leads us to wildly exaggerated perceptions of those we disagree with. It elides the diversity of our society and the myriad cross-cutting differences of geography, race, religion, class, gender, and generation that frequently complicate the polarization narrative. It turns out our “perception gaps” are especially acute on hot-button issues such as what we should teach students about race and our nation’s history, where we have much more in common than we think.

However, if we discern and appreciate the pluralism that we comprise in our various multitudes, then we can begin to lower our guard. An open posture signals to and leaves others free to let down their guard also. Curiosity, toleration, and forbearance can begin to supplant their opposites in a virtuous cycle. Even when we disagree, we can still recognize others as we want to be recognized–not as contemptible enemies, but as fellow citizens worthy of dignity and respect.

Denationalizing our politics and government

The polarization of our politics has proceeded hand-in-glove with the nationalization of our politics. A visitor from Mars would be forgiven for assuming that our national elections determined everything important in our system of government. But this perception would fail to grasp the actual division of labor and responsibilities within that system. While Washington’s sway is massive, it is limited in scope. As Ezra Klein has quipped, from a budgetary standpoint, the federal government is akin to “an insurance conglomerate protected by a large standing army.”[1]

Meanwhile, the bulk of the policies, funding, and services that directly impact the quality of our daily lives are determined at the state and local levels. These include policing, criminal justice, education, roads, mass transit, housing, zoning, economic development, public health, election administration, etc. The federal government may play more or less of a regulatory and underwriting role across these domains, but most of the governing in them occurs in states and localities.

If democracy means having a say in how we are governed, especially on issues that bear most directly on our lives, then our preoccupation with national politics and government is misplaced. We should focus more on our states and localities. The imbalance in our attention distorts our perceptions of where we actually have agency. We are much better positioned to influence politics and government at the local and state levels by dint of their closer proximity and smaller scale relative to the federal government.

Viewing our local and state governments as the building blocks of our democracy would, among other things, help offset the lack of trust in government we see nationally. A recent Pew Research Center survey affirmed a perennial pattern: we have more trust in levels of government closer to us. 66% of respondents reported a favorable view of their local government, and 54% did of their state government, compared to only 32% of the federal government.[2]

Breathing life into “the most important office”–that of citizen

Our election-centric conception of democracy leads us to understand ourselves primarily as voters who turn out—or not—to cast ballots every four years (every two for the really dedicated). In between, we have passive observer status. To be sure, some of us have become political hobbyists, to use Eitan Hersh’s apt term. Hobbyists spend an inordinate amount of time following and reacting to political news in the privacy of their own homes and/or in online spaces. But whether we are passive or active consumers of politics, our core function in the prevailing paradigm is periodically to vote in response to prompts from national candidates and the parties, pressure groups, and funders backing their campaigns.

However, we are not merely voters; we are citizens. As Louis Brandeis observed, “the most important office, and the one which all of us can and should fill, is that of private citizen. The duties of the office of private citizen cannot under a republican form of government be neglected without serious injury to the public.”[3] Voting in elections is certainly one of those duties, but there are other obligations of citizenship, and unlike voting, they fall to us every day of the year.

A robust but still non-exhaustive list of these additional obligations begins with the basic and formal requirements: obeying the laws, paying your taxes, and serving on juries when called. But such a list quickly extends to more intangible but no less essential obligations: being a good neighbor and community member; understanding how our system of government works, the fundamental principles underlying it, and the good and bad parts of our nation’s history; speaking up and finding effective ways to make your voice heard when you see those principles being violated; recognizing not only the legitimacy but also the inevitability and desirability of political opposition in a free society; and, as noted earlier, extending to others the mutual toleration and recognition they are due as fellow citizens–and that you rightly expect from them.

Put simplistically: do your part, agree to disagree, and don’t be a jerk. But we are finding it hard to follow even these precepts. The election-centric conception of democracy, by reducing us to mere voters, erodes the moral vocabulary of citizenship, not to mention the responsibility that many institutions previously assumed for forming citizens. It leaves us with a diminished to-do list as democratic actors. We have much less of a grasp on what we owe our fellow citizens, and on the inherent connections between their welfare and our own. This is bad for democracy, and it goads our feelings of loneliness and isolation.

In an article in this month’s Atlantic entitled “How America Got Mean,” David Brooks hits this nail squarely on the head:

“The most important story about why Americans have become sad and alienated and rude, I believe, is also the simplest: We inhabit a society in which people are no longer trained in how to treat others with kindness and consideration. Our society has become one in which people feel licensed to give their selfishness free rein. The story I’m going to tell is about morals. In a healthy society, a web of institutions—families, schools, religious groups, community organizations, and workplaces—helps form people into kind and responsible citizens, the sort of people who show up for one another. We live in a society that’s terrible at moral formation.”

Recovering “the meaning of democracy”

Democracy is the means through which we resolve our political disputes and determine what government does. But to reduce democracy to politics, and to the national elections, governing institutions, and policies that are the most prominent venues for politics, is to see only part of it. Such a truncation ignores the extent to which democracy in America is ultimately grounded in and supported by our civic culture–and the viewpoints and virtues it propagates (or fails to).

This idea is not a fanciful flight from current realities. Rather, it is a return to Tocqueville’s wisdom about the fundamental importance of what he referred to as mores or “habits of the heart” to the flourishing of democracy in America. Indeed, this was the central thesis of his masterful book on the topic.

A notable and more contemporary rendering of this idea came from E.B. White during World War II. Right before the 4th of July in 1943, White received an urgent request from the Writers’ War Board for a statement on “The Meaning of Democracy.” He was obliged and inspired to respond in The New Yorker as follows:

“Surely the Board knows what democracy is. It is the line that forms on the right. It is the don’t in don’t shove. It is the hole in the stuffed shirt through which the sawdust slowly trickles; it is the dent in the high hat. Democracy is the recurrent suspicion that more than half of the people are right more than half of the time. It is the feeling of privacy in the voting booths, the feeling of communion in the libraries, the feeling of vitality everywhere. Democracy is a letter to the editor. Democracy is the score at the beginning of the ninth. It is an idea which hasn’t been disproved yet, a song the words of which have not gone bad. It’s the mustard on the hot dog and the cream in the rationed coffee. Democracy is a request from a War Board, in the middle of a morning in the middle of a war, wanting to know what democracy is.”

This passage brings us around to our point of departure: A More Perfect Union’s long-term goal to “rebuild a strong, resilient democratic culture” of the sort White describes. It is tempting for civil society groups and the funders underwriting them to see this goal as something to back-burner until they have defeated clear and present dangers to democracy. That argument has held sway for several electoral cycles now, with rapidly accumulating opportunity costs in the form of foregone investments in our civic culture and infrastructure. No doubt there is important work to do in continuing to improve our election systems and checking authoritarian gambits. But the long-term goal cannot wait either. Until it is realized–and it is a task that could take decades–every election will bring new risks.

Finally, I readily acknowledge that the four reframings proposed above are blissfully unburdened by clear implications and concrete next steps–in this post anyway! I have shared them here as examples of why and how we need to reconsider key features of democracy we have come to overlook. This reframing will help us reboot democracy in America and rein in the current epidemic of loneliness. Seeing the big picture is invariably an important step in figuring out what to do next.

Notes

——————————

[1] For example, the Congressional Budget Office projects that in FY2023, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, military spending, and servicing the national debt will account for 66% of the $5.3 Trillion federal budget.

[2] Moreover, the stability of our low trust in government at the federal level masks huge partisan flip-flops. Our trust in the federal government has come to vary sharply based on whether our preferred party holds power. Our higher trust in local and state governments is also stable, but not because of fickle and off-setting partisan swings. It reflects continuities in our actual lived experience.

[3] For more background and the context for this quotation, and an interesting story about how President Obama subsequently used it in his speeches, see this post by Scott Campbell, Archivist of the Brandeis and Harlan papers at the University of Louisville Law Library.